Debbie and Danny Do Everything: Managing The Super Volunteer

Debbie and Danny Do Everything: Managing The Super Volunteer

Every booster club has one. Actually, if you're lucky, you have several. Let's call them Debbie and Danny Do Everything. The parent who shows up to everything, volunteers for everything, knows everything about every student and every activity. The one who's always first to respond to a call for volunteers and last to leave any event.

On paper, Debbie and Danny sound like a dream. And sometimes they are. But sometimes that eager, helpful parent becomes a problem. They're micromanaging other volunteers. They're burning themselves out. They're making decisions that should be made by the board. They're creating an atmosphere where other parents feel like there's no point in volunteering because Debbie or Danny has it all handled anyway.

And here's the danger nobody talks about: when Debbie or Danny finally leaves—when their kid graduates, when they move, when they burn out—the entire booster club can collapse. Because nobody else knows how to do what they did. Nobody else has the relationships they built. Nobody else has access to the accounts, the vendor contacts, the institutional knowledge. What looked like dedication was actually creating an organization completely dependent on one person.

Managing over-involvement is one of the most delicate challenges in booster club leadership because you're dealing with someone whose heart is usually in the right place. They genuinely care. They want to help. They're not trying to cause problems. But their level of involvement is creating both immediate issues and setting up your organization for potential disaster down the road.

Let's talk about how to recognize over-involvement, understand what drives it, and address it in ways that honor the person's contributions while protecting the long-term health of your organization.

Recognizing the Different Flavors of Over-Involvement

Not all over-involvement looks the same. Understanding what type you're dealing with will help you figure out the appropriate response.

The Control Enthusiast genuinely believes they're the only one who can do things correctly. They've been around for years, they know all the systems, and they're convinced that if they don't handle something personally, it will be done wrong. They're not trying to exclude others. They just don't trust anyone else to maintain their standards.

The Empty Nester is using the booster club to fill a void. Maybe their kids recently graduated or moved away. Maybe they're going through a difficult transition in their personal life. The booster club has become their primary source of purpose and social connection, and they've invested themselves heavily because they don't know what else to do with their time and energy.

The Rescuer sees problems everywhere and feels personally responsible for solving all of them. If there's a gap in volunteer coverage, they fill it. If something isn't getting done, they do it. They can't say no because they're convinced that if they don't step up, students will suffer. They're running on pure responsibility and guilt.

The Boundary-Challenged person simply doesn't recognize that there are limits to their role. They might be a volunteer who acts like a board member. They might be a board member who acts like they're in charge of everything. They might be a parent who's so involved that they're essentially trying to co-parent other people's children. They've lost perspective on where their authority and responsibility actually end.

The Social Connector is addicted to being in the middle of everything. They need to know all the information, be part of every conversation, and maintain relationships with everyone. Their over-involvement isn't about controlling outcomes. It's about maintaining their position at the center of the social network.

Each of these types requires a slightly different approach. But they all share one common thread: their involvement has crossed from helpful into problematic.

The Signs That Involvement Has Become Over-Involvement

How do you know when someone has crossed the line from being a dedicated volunteer to being over-involved? Here are the warning signs.

Other volunteers are stepping back or not volunteering at all because "Debbie has it covered" or "Danny's handling that." If one person's presence is suppressing participation from others, that's a problem. Your booster club needs depth and resilience, not dependence on a single person.

The person is making decisions that should involve others or require approval. They're spending money without authorization. They're communicating on behalf of the organization without running it by anyone. They're committing the group to things without checking if the group actually agrees.

They're showing signs of burnout but refusing to step back. They're irritable, exhausted, overwhelmed, but they keep taking on more. When you suggest they delegate or take a break, they insist they're fine, even though they're clearly not.

They're creating bottlenecks because they insist on being involved in everything. Projects stall because they haven't approved something or provided input. Other volunteers are waiting on them constantly. Nothing can move forward without their involvement.

They're struggling to separate their identity from their role. Their conversations are dominated by booster club activities. Their social circle is primarily or entirely booster club parents. They don't seem to have much of a life outside of this organization.

Drama seems to follow them. They're frequently involved in conflicts with other volunteers, disagreements with board members, or tensions with parents. It's not that they're malicious, but their level of involvement means they're constantly bumping up against boundaries and stepping on toes.

The Succession Crisis: What Happens When They Leave

Here's the scenario that plays out in booster clubs across the country every single year: Debbie or Danny Do Everything finally leaves. Their youngest kid graduates, they move to a different state, or they simply burn out and disappear. And suddenly, the booster club is in crisis.

Nobody knows the password to the spirit wear account. Nobody has the vendor contacts. Nobody understands how the concession stand inventory system works. The treasurer position sits empty for months because everyone assumes it requires Danny's level of expertise and time commitment. Fundraisers that Danny ran effortlessly for years fail spectacularly because nobody realized all the details he was managing behind the scenes.

The financial records are a mess because Debbie was the only one who understood her system. The website stops getting updated because Debbie was the only one with access. Volunteers who were intimidated by Debbie's standards don't step up because they assume they can't possibly fill her shoes. Parents who were frustrated by Danny's control decide this is their chance to completely reinvent everything, creating chaos and conflict.

Within six months, your booster club has gone from appearing strong and well-run to being on life support. Membership drops. Revenue declines. Key programs get cut. Board positions go unfilled. The organization that seemed invincible when Debbie or Danny was running things turns out to have been a house of cards.

This isn't hypothetical. This is the predictable consequence of allowing one person to become indispensable. The irony is that Debbie and Danny often believe they're strengthening the organization through their tireless efforts. They don't realize they're actually creating fragility.

Your job as a leader isn't just to manage current over-involvement. It's to protect your organization from the inevitable day when that over-involved person is gone. Because they will be gone eventually. Kids graduate. People move. Life changes. And your booster club needs to be able to survive and thrive without any single person.

Understanding the Why Behind the Behavior

Before you address over-involvement, it helps to understand what's driving it. Most people don't wake up and decide to become problematically over-involved. They slide into it gradually, often with the best intentions.

Some people genuinely don't realize they're doing anything wrong. They think they're being helpful. They see needs and fill them. They don't understand that their helpfulness is having negative effects because no one's told them directly.

Others are driven by anxiety. They worry that if they're not constantly involved and vigilant, something will go wrong. This often stems from past experiences where things actually did go wrong, or from personality traits that make it hard for them to trust others or tolerate uncertainty.

For some, it's about identity and self-worth. Their involvement in the booster club has become their primary source of validation and purpose. They measure their value by how much they contribute and how indispensable they are. Stepping back feels like losing their identity.

Sometimes it's about control needs that stem from other areas of their life where they feel out of control. Maybe their work situation is uncertain. Maybe their marriage is struggling. Maybe they're dealing with health issues. The booster club becomes the place where they can exercise control and feel capable.

And sometimes people are simply responding to genuine need combined with their own personality traits. If your booster club is chronically understaffed and someone with high energy and a strong sense of responsibility steps into that vacuum, over-involvement is almost inevitable.

Understanding the why doesn't excuse problematic behavior, but it does help you approach the conversation with empathy rather than judgment.

The Conversation You're Avoiding Having

Most booster club leaders know they need to address over-involvement but keep putting it off. They're afraid of hurting the person's feelings, creating conflict, or losing a valuable volunteer. So they don't say anything, the behavior continues, and the problems compound.

Here's what you need to understand: not addressing the issue is not kind. It's not kind to the person who's burning themselves out. It's not kind to other volunteers who are being shut out or steamrolled. It's not kind to your organization, which is becoming dependent on one person in an unhealthy way. And it's not kind to you, because the stress of managing around this person's behavior is exhausting.

When you finally have the conversation, here's how to approach it. Choose a private setting where you won't be interrupted. This isn't a conversation for a hallway after a meeting or a quick phone call while you're both distracted. Set aside dedicated time and space.

Start with appreciation. Acknowledge their contributions and their dedication. Be specific about things they've done well. This isn't just buttering them up. It's recognizing that they genuinely have contributed value, even if their current level of involvement has become problematic.

Then describe the specific behaviors you're concerned about, without making it personal. Don't say "You're too controlling." Say "I've noticed that you're taking on responsibilities that aren't part of the volunteer coordinator role, and I'm concerned about how that affects other volunteers' ability to contribute."

Focus on impact rather than intent. You're not questioning their motives or their character. You're describing the effects of their behavior. "When volunteers sign up for a task and then are told you're handling it instead, they feel like their help isn't wanted, and they stop volunteering."

Use collaborative language to problem-solve. "I want to figure out how we can make sure critical tasks get done while also creating space for other people to contribute. What ideas do you have about how we could do that?" This frames it as a shared challenge rather than you criticizing them.

Be prepared for defensiveness. People don't usually respond well to hearing that their helpfulness is problematic. They might push back, justify their behavior, or get emotional. Stay calm, stay compassionate, but don't back down from the core message.

Set clear boundaries and expectations going forward. Be specific about what needs to change. "Moving forward, I need you to check with me before committing the organization to any expenses over $100" or "I need you to step back from the concession stand committee and let the new coordinator take the lead."

Strategies for Redirecting Debbie and Danny's Energy

Sometimes a conversation alone isn't enough. You need practical strategies to create boundaries and redirect energy in healthier directions.

Create defined roles with clear scope. If Debbie or Danny has been operating without clear limits, give them a specific role with explicit boundaries. "You're the spirit wear coordinator, which means you manage the online store and work with the vendor. It doesn't include making decisions about which fundraisers we run or how we handle finances."

Implement approval processes and authorization requirements. If someone's been making decisions they shouldn't make, create systems that require multiple people to sign off. This isn't about not trusting them. It's about organizational health and sustainability.

Actively recruit and develop other volunteers to create redundancy. The best way to address one person being over-involved is to get more people involved. If the spirit wear program is dominated by Debbie, recruit and train a co-coordinator. If Danny's running the concession stand single-handedly, build a team. This protects you from the succession crisis when they eventually leave.

Assign the over-involved person to mentor or train others. This redirects their energy into something valuable while naturally reducing their direct involvement and building institutional knowledge. "Danny, I know you have tremendous expertise in fundraising. Would you be willing to develop a training guide for new board members so they can learn from your experience? And let's have you mentor a co-chair who can eventually take over."

Create rotation policies for key roles. Term limits and rotation requirements prevent anyone from becoming indispensable or entrenched. This isn't targeted at one person. It's just good organizational practice.

Celebrate and encourage their stepping back. When they do delegate or let others handle something, make a big deal about it in a positive way. "I really appreciated how you let the new volunteer run the spirit wear table tonight. That gave them confidence and showed them we trust them."

When the Person Won't Change

Sometimes, despite your best efforts, the person won't modify their behavior. They continue to over-function, micromanage, and create problems. At that point, you have some harder decisions to make.

You might need to remove them from a leadership position. This is nuclear option territory, and it should only happen after you've clearly communicated expectations and given them a genuine opportunity to change. But if someone is actively harming your organization and refuses to adjust, you may need to ask them to step down from their formal role.

You might need to work around them. If they won't stop trying to control the concession stand but they're not actually in charge of the concession stand, you focus your energy on empowering the person who is in charge and protecting them from interference. You create structures and processes that don't require the over-involved person's input or approval.

You might need to accept some level of involvement while containing it. Not every situation requires a complete solution. Sometimes the best you can do is keep the person from causing major problems while recognizing they're not going to become the perfectly balanced volunteer you wish they were.

In extreme cases, you might need to tell someone they're no longer welcome to volunteer. This is rare and should be reserved for situations where someone's behavior is genuinely toxic or harmful. But it's an option that exists if someone absolutely refuses to respect boundaries and their presence is driving away other volunteers or creating a hostile environment.

The Cultural Side of Over-Involvement

Individual over-involvement is often a symptom of organizational culture issues. If your booster club consistently produces over-involved volunteers, you probably have systemic problems.

Maybe you're chronically understaffed, so anyone with energy and time naturally ends up doing too much because there's too much work for too few people. The solution isn't to tell those people to do less. It's to recruit more volunteers.

Maybe you don't have clear structures and boundaries, so people have to create their own boundaries, and some people create very expansive ones. The solution is to clarify roles, responsibilities, and decision-making authority.

Maybe you have a culture that glorifies overwork and treats burnout as a badge of honor. People compete to be the most dedicated, the most involved, the most indispensable. The solution is to actively model and reward healthy boundaries.

Maybe you're not recognizing and celebrating the quiet contributions of people who volunteer in sustainable ways. All the attention goes to the person who's at every event doing everything, while the person who reliably shows up for their assigned shift and then goes home gets no recognition. The solution is to actively appreciate balanced involvement.

Building a healthy culture means making it easier to volunteer in right-sized ways. Clear job descriptions, reasonable time commitments, good onboarding and training, and explicit permission to say no all help prevent the conditions that create over-involvement.

Supporting Someone Who's Stepping Back

When someone does start to reduce their involvement, whether voluntarily or because you've asked them to, they often need support through that transition.

Acknowledge that it might be hard for them. Stepping back from something you've poured yourself into isn't easy. It can feel like rejection or failure, even when it's the healthy choice. Recognize their feelings without trying to talk them out of those feelings.

Help them find other outlets for their energy and need for contribution. If someone's been getting all their social connection and sense of purpose from the booster club, they need to build those things elsewhere. Encourage them to explore other interests, reconnect with old friends, or get involved in other ways that are more sustainable.

Keep them included in appropriate ways. Just because someone needs to reduce their involvement doesn't mean they should be completely shut out. They can still attend events. They can still be part of the community. They just need to have boundaries around their level of responsibility.

Check in with them periodically. Transitioning from being highly involved to being less involved can be lonely and disorienting. A simple "how are you doing?" or "I've been thinking about you" can mean a lot.

Prevention Is Better Than Intervention

The best way to manage over-involvement is to prevent it from happening in the first place. This means being proactive about organizational health and volunteer culture.

Set clear expectations from the beginning about roles and time commitments. When someone volunteers, tell them explicitly what they're signing up for and what they're not signing up for. Don't let people drift into expanded roles without clear conversation.

Model healthy boundaries yourself. If you're the board president and you're responding to emails at midnight and working on booster club stuff seven days a week, you're teaching everyone that's the expectation. Show people what sustainable involvement looks like.

Create multiple points of connection and leadership. Don't let any single person become the sole repository of knowledge or the only one who knows how to do critical tasks. Document processes, cross-train people, and distribute responsibility.

Regularly assess volunteer workload and well-being. Check in with your active volunteers about how they're doing, what's working, what's overwhelming them. Don't wait for them to burn out or become problematic before you notice they're taking on too much.

Celebrate people who set boundaries. When someone says no to a request or declines to take on additional responsibility, respond positively. Thank them for their honesty. Appreciate what they are doing rather than pressuring them about what they're not doing.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Here's something that makes people uncomfortable: sometimes Debbie or Danny Do Everything is you. Maybe you're reading this article and recognizing yourself in these descriptions. Maybe you're the one who can't let go, who insists on being involved in everything, who's stretched too thin but can't seem to stop.

If that's you, please hear this with compassion: your over-involvement isn't helping the way you think it is. You might be getting things done, but you're probably also preventing others from contributing, setting yourself up for burnout, and making your organization fragile because it depends too heavily on you. When you eventually leave—and you will leave eventually—you might be leaving behind an organization that can't function without you.

Stepping back isn't abandoning the organization. It's giving it space to develop depth and resilience. It's allowing other people to discover their own capacity to contribute. It's modeling healthy boundaries for everyone around you. And it's ensuring that the booster club you've worked so hard to build can survive and thrive after you're gone.

And it's giving yourself permission to have a life that isn't consumed by one organization. The booster club is important. But it's not more important than your health, your family, your other relationships, and your own well-being.

So if you're realizing right now that you are Debbie or Danny Do Everything, here's what you need to do: ask for help. Today. Not next month, not after this season ends, not when things calm down. The health of your booster club depends on distributing responsibility across multiple people. And your own health depends on stepping back before you burn out completely. It's time.

A Final Word on Compassion

Managing over-involvement requires holding two truths simultaneously. The first truth is that Debbie or Danny's behavior is causing problems and needs to change. The second truth is that they usually care deeply, mean well, and are trying to help.

You can honor both of these truths. You can insist on boundaries while appreciating contributions. You can protect your organization's health and long-term sustainability while caring about an individual volunteer's well-being. You can make hard decisions with kindness.

The goal isn't to shut people down or make them feel bad about their enthusiasm. The goal is to create an organization where lots of people can contribute in sustainable ways, where no one burns out, where institutional knowledge is shared rather than hoarded, and where the booster club can survive and thrive when any individual moves on.

Some of your best volunteers will be people who once were over-involved and learned to channel their energy more effectively. Don't write someone off because they initially struggled with boundaries. Give them the feedback and support they need to find a healthier level of involvement.

And remember that this is an ongoing challenge, not a one-time fix. Volunteer dynamics shift. New people join. Life circumstances change. What works this year might not work next year. Stay attentive, stay flexible, and keep having the honest conversations that keep your organization healthy.

Because at the end of the day, you're all on the same team. You're all there for the students. The challenge is figuring out how everyone can contribute their gifts without anyone sacrificing their health and well-being in the process, and without creating an organization so dependent on Debbie or Danny Do Everything that it can't function when they're gone. That's worth the difficult conversations

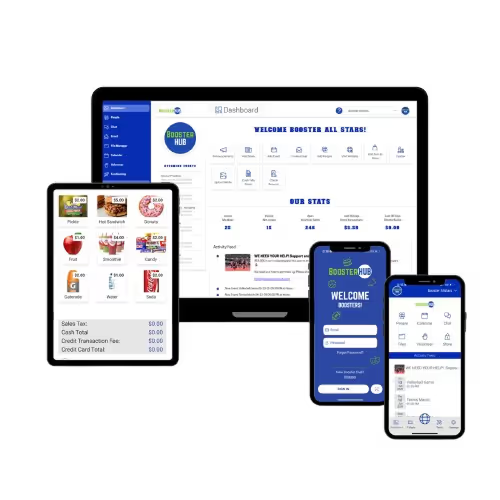

Simplify Communications from App to Website

.avif)